Pace Yourself

By M.G. Knight

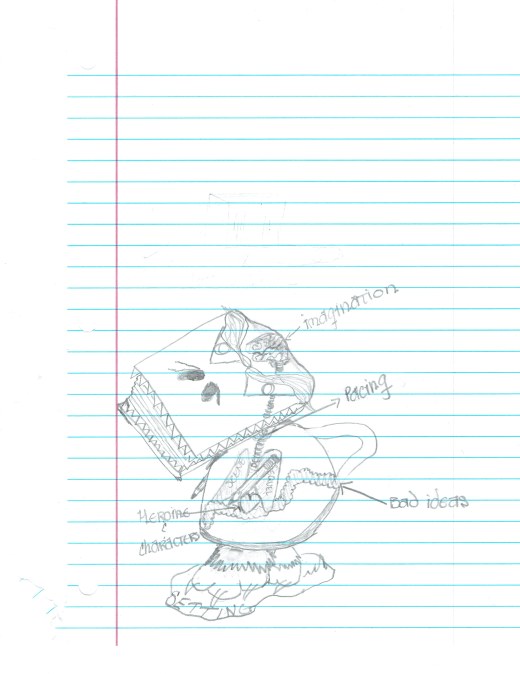

It’s such a seemingly trivial, overused term, but pacing is like the magic wand of writing: If you wave that thing incorrectly, you’ll ruin the entire story. If you wave it right, well, you might just cast a spell on your audience.

Pacing leads to those all-too-familiar feelings we get when someone is spitting information at us without pauses or when a politician ends every other word with a long “um.” It’s the reason we can empathize with the Fellowship after Gandalf dies and why we feel utterly exhausted if we read a book with non-stop action. Pacing interferes with nearly every aspect of story writing. Pacing is a pigheaded instigator.

with non-stop action. Pacing interferes with nearly every aspect of story writing. Pacing is a pigheaded instigator.

Most writers have a natural inkling of pacing, of knowing where a beat should be included or when their audience is being induced into a coma. Even so, it usually takes work to create a flawless symphony of words, time, and transition throughout the page. To avoid flat-lining your readers, it’s important that an author take a step back to look at her story as a whole in the revision process—and, of course, this includes the illusion of time.

As Jeff Vandermeer points out so eloquently, your story is a creature. It rests, it sleeps and gets sick, it exercises—and it breathes just like you and I. As such, that breathing changes regularly in response to the scenes and plot dynamics of its innards. If the protagonist—your story’s heart—is in trouble, your poor story is probably experiencing a shortness of breath akin to a panic attack. If it experiences grief, your little monster will slow down to take it all in, to react and recognize the pain after the initial jolt of change. If a joyous scene occurs, its little lungs will be contracting and expanding as it tries to send that fluttering feeling from its furry story claws to the top of its bound, paper head.

The writing follows suit. It speeds up with your story’s pulse, with each lungful of air or gasp of breath. Therefore, you can think of pacing as a way your story would react to what is occurring inside it.

Consider.

Beat.

Pacing is your story’s lungs breathing in a scene for the first time.

Beat.

It is the oxygen entering your story, flowing through its capillaries and into a narrative’s lifeblood.

Beat.

Pacing is your story’s heart, softly beating against its chest.

So next time you wonder if you are moving too quickly or too slowly, if you’re losing the audience or vexing them with incessant action, stop. Listen. How is your story breathing? What is its heartbeat telling you?

The answers lie there.

Excellent blog on pacing!!! Thanks for describing it clearly and succinctly. Love this: Pacing is your story’s heart, softly beating against its chest.

LikeLike

Yay! Thanks, Dianne. I think pacing can also be akin to stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting . . . but the heart thing sounds much brighter.

LikeLike